What is the GAF (Geographic Adjustment Factor) in Healthcare?

The Geographic Adjustment Factor (GAF) is the combined regional payment adjustment used by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to modify physician reimbursement under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS). It represents the aggregate effect of the three Geographic Practice Cost Index (GPCI) components—Work GPCI, Practice Expense GPCI, and Malpractice GPCI—on overall payment for a specific Medicare locality.

In simple terms, GAF is a single composite number that shows how much more or less a physician in one area is paid compared to the national average. A GAF above 1.00 indicates higher-than-average costs (and higher reimbursement), while a GAF below 1.00 reflects lower-cost regions.

GAF provides a practical summary of geographic payment variation without requiring analysis of each individual GPCI component. CMS publishes annual GAF tables for every Medicare payment locality, which are used by payers, consultants, and policymakers to benchmark physician compensation levels across the U.S.

Because GAF integrates all three cost factors, it plays an essential role in payment modeling, contract negotiation, and workforce planning. It also helps researchers and advocacy groups evaluate regional equity and access to care under the MPFS framework.

Key Components of the Geographic Adjustment Factor (GAF)

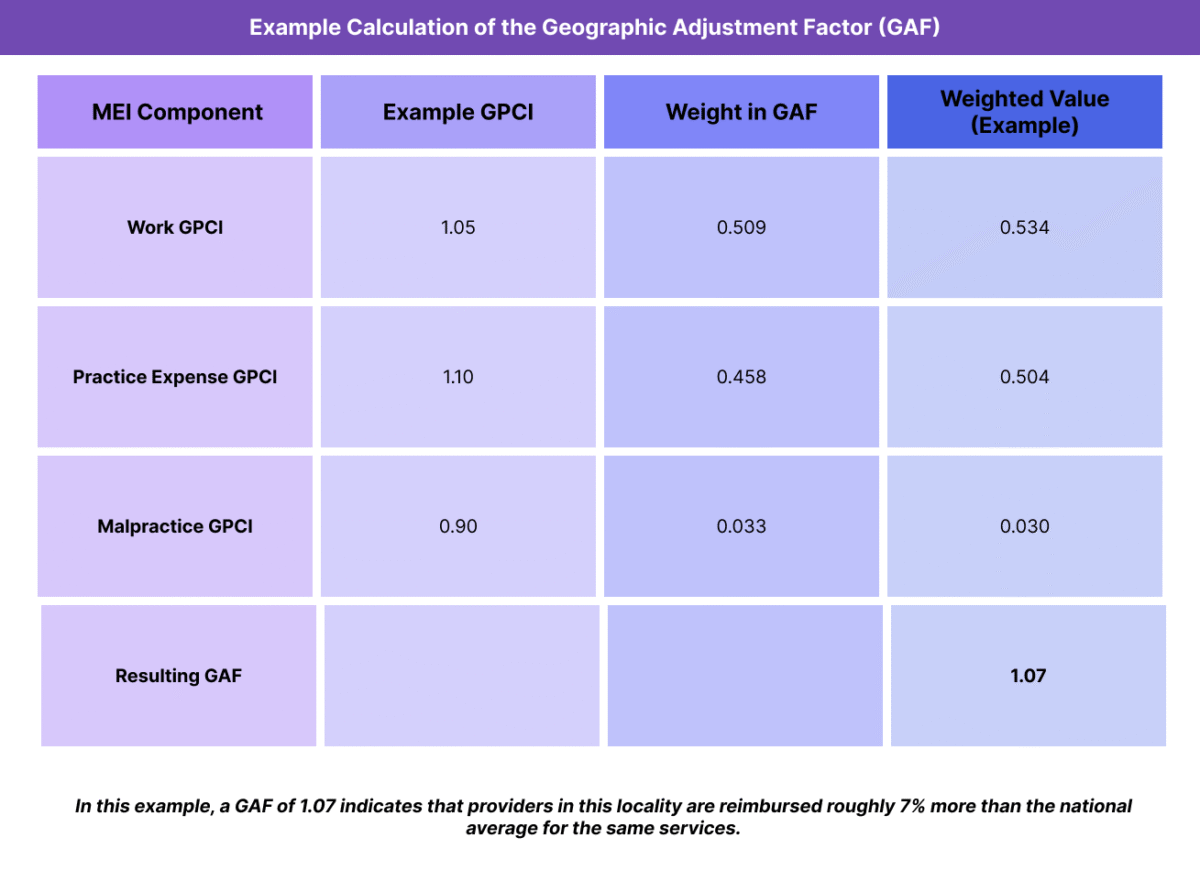

The Geographic Adjustment Factor (GAF) is calculated by combining the three Geographic Practice Cost Index (GPCI) components used in the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS): Work GPCI, Practice Expense (PE) GPCI, and Malpractice (MP) GPCI. Together, these represent the full cost profile of providing medical services in a given region.

Each GPCI is assigned a weight based on its proportion in the Medicare payment formula, ensuring that the GAF reflects realistic practice cost distribution across the country.

1. Work GPCI

- Adjusts for local physician labor costs and compensation levels.

- Accounts for roughly 51% of the total payment weight in GAF.

- Derived from regional wage data collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

2. Practice Expense (PE) GPCI

- Reflects office overhead, staff wages, supplies, and rent.

- Contributes approximately 45% to the total GAF calculation.

- Often the largest driver of variation between localities.

3. Malpractice (MP) GPCI

- Captures regional differences in liability insurance premiums.

- Represents roughly 4% of the total GAF weight.

- Typically has minimal impact nationally but is significant in high-risk states.

Formula:

GAF = (Work GPCI × 0.509) + (PE GPCI × 0.458) + (MP GPCI × 0.033)

This weighted composite produces a single value used to compare or adjust physician reimbursement rates among Medicare payment localities.

Why GAF Matters

- Simplifies the interpretation of regional payment variation.

- Allows policymakers and payers to compare local cost environments at a glance.

- Provides a useful tool for forecasting reimbursement trends and analyzing equity in access to care.

How the Geographic Adjustment Factor (GAF) Works in Practice

The Geographic Adjustment Factor (GAF) is applied automatically within the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) to determine the final reimbursement amount for physician services. It reflects how the aggregate regional cost structure (labor, overhead, malpractice) modifies the national payment rate for a given CPT or HCPCS code.

While most users interact with individual GPCI values, the GAF serves as the simplified summary measure used by CMS, providers, and analysts to understand overall payment variation between Medicare localities.

Step 1: CMS Establishes Local GPCI Values

- CMS collects regional data on wages, rent, supplies, and insurance premiums from federal and industry sources such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and Medical Liability Monitor.

- Separate GPCI values for Work, Practice Expense, and Malpractice are calculated for each Medicare payment locality.

- These values represent local deviations from the national average (1.00 baseline).

Step 2: Combine GPCI Components to Produce GAF

- The GAF formula applies CMS’s standard weights to each component:

GAF = (Work GPCI × 0.509) + (PE GPCI × 0.458) + (MP GPCI × 0.033) - The resulting composite value reflects the overall cost environment of the locality.

- GAF values are published annually in CMS’s MPFS Final Rule and associated Geographic Adjustment Tables.

Step 3: Apply GAF to Medicare Payment Calculations

- GAF is not used directly in claim-level math but serves as a summary multiplier of the total payment rate relative to the national average.

- For instance, a GAF of 1.05 means that providers in that locality receive approximately 5% higher reimbursement than the national baseline for the same service.

- Conversely, a GAF of 0.96 indicates that payments are about 4% lower than average.

Step 4: Provider and Payer Use Cases

- Healthcare organizations use GAF values to forecast Medicare revenue across markets or when opening new practice locations.

- Payers and consultants rely on GAF data for rate-setting, contract modeling, and geographic benchmarking.

- Policymakers use GAF comparisons to identify regional disparities and evaluate payment fairness in rural or high-cost areas.

Step 5: Review and Update Process

- CMS updates GPCI values (and thus GAF) every three years, with interim adjustments as needed.

- Annual GAF updates are included in the MPFS Final Rule, along with public documentation of data sources, weighting, and locality definitions.

- Providers can view current and historical GAF values in CMS’s Medicare Geographic Adjustment Factor tables.

GAF Billing, Reimbursement, and System Limitations

The Geographic Adjustment Factor (GAF) serves as a key benchmarking tool for understanding regional variation in Medicare reimbursement under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS). While GAF simplifies the complexity of the underlying Geographic Practice Cost Index (GPCI) system, it also inherits its methodological limitations and equity challenges, which can significantly influence provider compensation and access to care.

How GAF Influences Reimbursement

- GAF reflects the aggregate effect of local cost variation on Medicare payment rates.

- Regions with higher GAF values (>1.00) receive proportionally higher reimbursements for the same service, reflecting elevated wage or facility costs.

- Conversely, areas with lower GAF values (<1.00) are reimbursed at a reduced rate, typically corresponding to lower living and operating costs.

- These adjustments are intended to create geographically equitable compensation, ensuring that physician payments align with local cost structures.

Example:

If a national payment rate for a service is $100 and a locality’s GAF is 1.05, the adjusted payment rate becomes $105 for that area.

Impact on Medicare Payment Systems

- GAF values influence reimbursement across thousands of CPT and HCPCS codes under the MPFS.

- They also provide a benchmark for commercial payer negotiations, as many private insurers use GAF-influenced models to calibrate regional rate differentials.

- Policymakers use GAF to analyze the geographic distribution of Medicare spending, workforce distribution, and potential inequities in care access.

Limitations and Ongoing Challenges

-

Broad Locality Definitions

Many Medicare payment localities cover large and economically diverse regions, meaning the same GAF applies to both urban and rural areas within that locality.

This lack of granularity can underrepresent cost variation within individual markets.

-

Data Lag and Static Weights

GAF relies on GPCI data that may lag 1–2 years behind real-world cost changes, especially during periods of inflation.

The standard GAF formula uses fixed weighting factors (Work 0.509, PE 0.458, MP 0.033) that may not accurately reflect current practice economics or specialty differences.

-

Urban–Rural Disparities

High-cost metropolitan areas often have higher GAF values, attracting greater physician income and workforce density.

In contrast, rural and low-GAF areas may struggle to recruit or retain providers, perpetuating geographic inequities in access to care.

RHCs and CAHs, which use cost-based reimbursement models like AIR, are exempt from direct GAF impact but still face indirect effects in workforce and contract negotiations.

-

Policy and Legislative Constraints

Adjusting GAF methodology requires congressional authorization because it is embedded in statutory payment policy.

Proposed reforms—such as region-specific weighting or alternative locality designations—often stall due to complexity and budget neutrality requirements.

Calls for Reform

- Advocacy groups and researchers have suggested modernizing GAF to reflect more granular regional data, updated cost weights, and dynamic adjustment factors that respond to real-time inflation.

- Others propose incorporating Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) or equity indices to better align GAF with Medicare’s access and fairness goals.

- CMS continues to evaluate GAF and GPCI methodologies as part of broader Medicare payment modernization efforts.

GAF and Its Impact on Quality, Access, and Health Equity

The Geographic Adjustment Factor (GAF) influences more than just payment rates — it shapes the distribution of physicians, practice viability, and access to care across the United States. Because GAF aggregates all three Geographic Practice Cost Index (GPCI) components into a single locality-wide metric, it plays a defining role in how equitably Medicare funds are distributed across regions.

While GAF supports fairness in theory, its broad application and reliance on averaged data can also reinforce systemic disparities in workforce placement and service availability.

Promoting Regional Payment Fairness

- GAF ensures that providers in high-cost areas (with higher rents, wages, and malpractice costs) are reimbursed at proportionally higher rates.

- This adjustment maintains practice sustainability and patient access in expensive urban markets where operational costs could otherwise exceed Medicare payments.

- The model was designed to prevent physicians in cost-intensive cities from being underpaid relative to those in lower-cost areas.

Challenges to Equity and Rural Access

- The flip side of GAF-based adjustment is that low-cost, low-GAF regions receive systematically lower payments.

- In practice, this can discourage providers from establishing or maintaining practices in rural and underserved communities, where margins are already thin.

- The static locality boundaries used to define GAFs also mask intra-regional disparities, meaning a small-town clinic may receive the same GAF adjustment as a major urban hospital in the same payment zone.

- These structural imbalances can reduce patient access and limit care continuity in the very regions where equity-focused investment is most needed.

Influence on Provider Distribution and Workforce Stability

- Because higher GAF values correlate with higher reimbursement, they influence physician migration patterns, often concentrating specialists in high-GAF urban centers.

- This trend reinforces urban-rural workforce imbalances, with rural areas relying more heavily on cost-based reimbursement systems like the All-Inclusive Rate (AIR) for sustainability.

- The result is a persistent disparity in provider-to-patient ratios, especially in primary care, behavioral health, and geriatrics.

Policy Implications for Equity Reform

CMS and policymakers are increasingly examining whether GAF and its GPCI components truly reflect the current economic and social realities of healthcare delivery.

Proposals for reform include:

- Introducing sub-locality adjustments or granular market segmentation to refine GAF accuracy.

- Incorporating Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) or workforce access indicators into geographic adjustment formulas.

- Aligning GAF methodology with broader value-based payment and equity performance frameworks.

- These strategies aim to preserve fiscal fairness while addressing access gaps and inequities in underserved regions.

Balancing Cost Equity with Access Equity

- GAF has historically focused on cost parity rather than access parity — equalizing payment for cost of care, not for availability of care.

- Future reforms may expand the concept to balance both: ensuring that providers are compensated fairly and that patients, regardless of location, can access comparable levels of care.

- By modernizing GAF to reflect both cost and care equity, CMS could better align reimbursement with its mission to promote quality, sustainability, and universal access.

Frequently Asked Questions about the GAF

1. What is the Geographic Adjustment Factor (GAF)?

The Geographic Adjustment Factor (GAF) is the combined regional payment adjustment used by CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services) to modify physician reimbursement under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS). It represents the aggregate impact of the three Geographic Practice Cost Index (GPCI) components — Work, Practice Expense, and Malpractice — in a single, composite value for each Medicare payment locality.

2. How is the GAF calculated?

The GAF is calculated using the formula:

GAF = (Work GPCI × 0.509) + (Practice Expense GPCI × 0.458) + (Malpractice GPCI × 0.033)

These weights reflect the proportional influence of each cost component in Medicare’s total payment structure. The resulting composite shows how much higher or lower a locality’s reimbursement is relative to the national average (1.00 baseline).

3. What does a GAF value represent?

A GAF value expresses how regional practice costs affect physician reimbursement.

- GAF > 1.00: Payments are higher than the national average.

- GAF < 1.00: Payments are lower than the national average.

For example, a GAF of 1.05 means a 5% higher payment rate for the same service compared to the national baseline.

4. What is the difference between GAF and GPCI?

- GPCI (Geographic Practice Cost Index): Three separate indices (Work, Practice Expense, and Malpractice) that adjust specific cost components of physician reimbursement.

- GAF (Geographic Adjustment Factor): A single composite number that summarizes all three GPCIs into one weighted value for simplicity.

In short, GAF is the summary metric, while GPCI provides the detailed inputs.

5. How often is the GAF updated?

GAF values are updated every three years when CMS revises GPCI data. The updates incorporate new regional cost data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), insurance market surveys, and other sources. Interim adjustments may be made if Congress or CMS mandates changes to specific locality definitions or weighting methods.

6. How does GAF affect Medicare reimbursement?

GAF directly affects how much Medicare reimburses physicians for the same service in different regions. A higher GAF increases total payment under the MPFS formula, while a lower GAF reduces it. Although GAF itself isn’t used on individual claims, it’s essential for understanding regional payment equity and contract modeling.

7. Why is GAF important for healthcare equity and workforce planning?

GAF helps promote payment fairness by aligning reimbursement with regional costs, but it can also widen urban–rural access disparities if not periodically updated or localized. Policymakers use GAF data to track where reimbursement differences may impact provider availability, practice sustainability, and patient access — key drivers of health equity.