What Is the Upper Payment Limit (UPL)?

The Upper Payment Limit (UPL) is a federal regulatory ceiling established by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to cap the total amount of Medicaid payments that a state may make to a specific class of healthcare providers. It defines the maximum reimbursement a state can provide under Medicaid—ensuring that total payments do not exceed what Medicare would have paid for equivalent services.

UPL calculations are typically applied to institutional providers such as hospitals, nursing facilities, and clinics, and are used to determine the allowable supplemental payments states can make to providers beyond base Medicaid rates. States must demonstrate, through detailed UPL demonstrations and audits, that their aggregate payments remain within the established federal limits.

Authorized under 42 CFR §447.272–§447.321, the UPL framework serves as a key mechanism for maintaining fiscal integrity in Medicaid financing. States often use UPL programs to enhance payments to public or private hospitals—subject to CMS approval through State Plan Amendments (SPAs)—while balancing access, quality, and compliance.

By aligning state Medicaid reimbursements with Medicare-equivalent benchmarks, UPL programs help ensure budget neutrality and prevent overpayment risk, while still allowing flexibility for states to address local care delivery costs and provider sustainability.

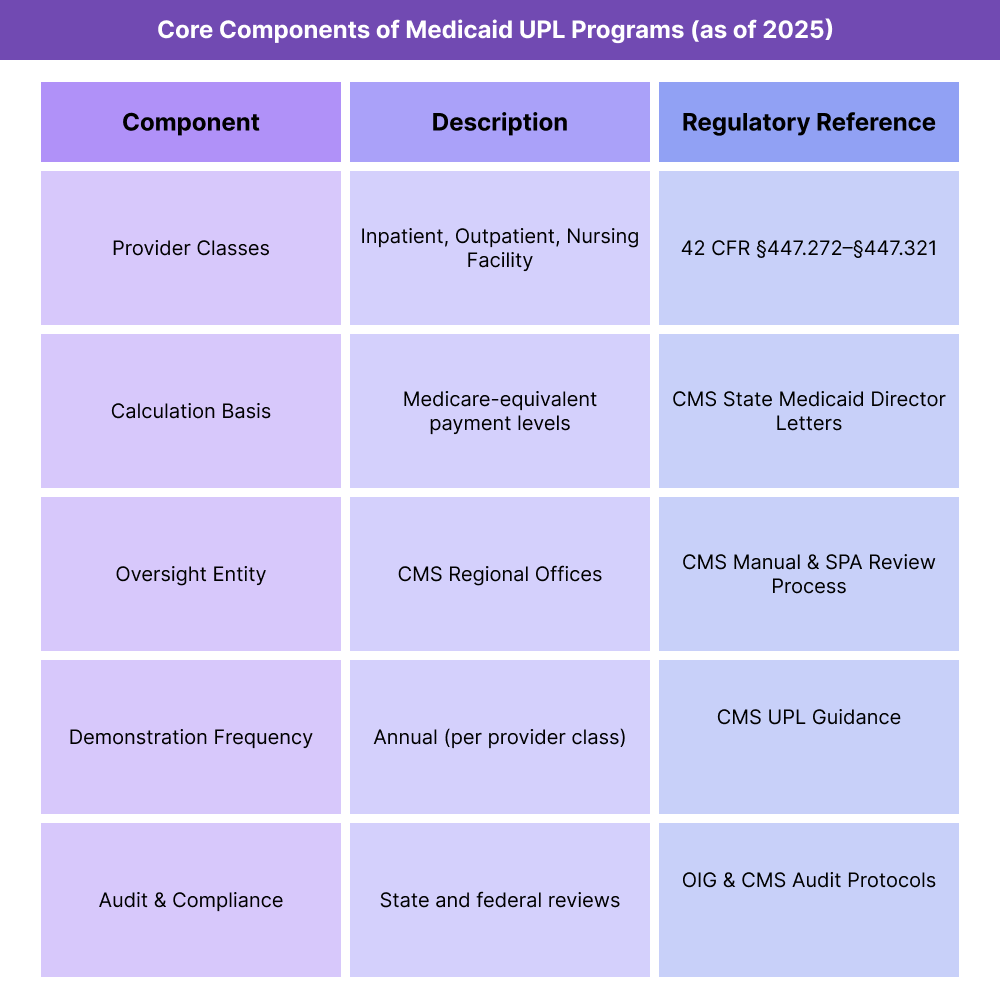

Key Components of the Upper Payment Limit (UPL))

The Upper Payment Limit (UPL) is a foundational element of Medicaid financing and reimbursement policy, defining the maximum aggregate payment a state may provide to certain classes of providers. It ensures that total Medicaid payments do not exceed the Medicare equivalent amount for the same services, preserving fiscal integrity and regulatory compliance under CMS oversight.

1. Provider Classes Under UPL

UPL rules are structured around provider classifications, each with distinct federal ceilings and demonstration requirements.

The three primary classes recognized by CMS are:

- Inpatient Hospitals – Includes state, non-state government, and private hospitals providing inpatient services to Medicaid beneficiaries.

- Outpatient Hospitals and Clinics – Covers outpatient departments, rural health centers, and federally qualified health centers where applicable.

- Nursing Facilities – Encompasses long-term care and skilled nursing facilities reimbursed under state Medicaid plans.

Each provider class must be evaluated separately in UPL calculations, and states are required to submit UPL demonstrations showing compliance for each class annually.

2. Calculation and Methodology

- The UPL calculation estimates what Medicare would have paid for the same volume and mix of services provided to Medicaid patients.

- States may use Medicare cost reports, claims modeling, or statistical sampling to derive UPL benchmarks.

- CMS permits flexibility in methodology, but states must use actuarially sound, documented approaches subject to federal audit.

- Payment models must distinguish between base payments (for services rendered) and supplemental payments (to address funding gaps or special local needs).

3. CMS Oversight and State Plan Amendments (SPAs)

- Any UPL payment structure must be approved by CMS through a State Plan Amendment (SPA).

- States must maintain auditable documentation, submit annual UPL demonstrations, and update methodologies if payment structures change.

- CMS Regional Offices review UPL submissions for each provider class, verifying compliance with 42 CFR §447.272–§447.321.

- Noncompliance can result in federal disallowances, requiring repayment of excess federal funds.

4. Relationship to Other Medicaid Financing Mechanisms

- UPL programs operate alongside—but are distinct from—other Medicaid supplemental payment initiatives, including:

- DSH (Disproportionate Share Hospital) Payments – Focused on hospitals serving a high volume of low-income patients; separate from UPL limits.

- Intergovernmental Transfers (IGTs) and Certified Public Expenditures (CPEs) – Used by states to fund their share of Medicaid payments and often integrated into UPL financing structures.

- Managed Care UPLs – CMS permits special calculations for non-risk managed care arrangements, ensuring parity with FFS benchmarks.

- Together, these mechanisms allow states to sustain provider participation without exceeding federal reimbursement thresholds.

5. Transparency, Auditing, and Compliance

- States must retain supporting data for UPL calculations for at least three years and make it available upon request to CMS or OIG.

- Independent audits are recommended to validate compliance and ensure no duplication of payments across funding streams.

- CMS encourages public posting of UPL demonstration summaries to improve transparency and promote accountability in Medicaid payment systems.

6. Policy Intent and Fiscal Impact

The UPL framework safeguards against excessive Medicaid reimbursements while allowing states to strategically allocate supplemental funding to underfunded providers. Properly structured, UPL programs balance budget control, provider sustainability, and equitable access—a critical factor in maintaining Medicaid’s financial integrity.

How Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) Work in Practice

Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) are the operational backbone of Medicare’s fee-for-service (FFS) payment system. They serve as CMS’s field-level administrators—turning national policy, coding rules, and payment formulas into real-time claims decisions and provider reimbursements.

Every healthcare provider or supplier participating in Medicare interacts with their assigned MAC for claims processing, enrollment, coverage guidance, and appeals.

Step 1: Provider Enrollment and Credentialing

- Before billing Medicare, a provider must enroll with their regional MAC through PECOS (Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System).

- The MAC verifies credentials, practice ownership, and compliance with CMS participation requirements.

- Once approved, the MAC assigns a Provider Transaction Access Number (PTAN) and activates billing privileges.

Step 2: Claims Submission and Processing

Providers submit electronic claims (837P for professional, 837I for institutional) directly to their MAC via Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) or clearinghouse.

The MAC applies CMS rules, such as:

- The current Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS)

- Applicable Geographic Practice Cost Index (GPCI)

- Conversion Factor (CF) for the current year

- Coverage and documentation requirements based on National Coverage Determinations (NCDs) and Local Coverage Determinations (LCDs)

The MAC’s claims adjudication system validates coding, eligibility, modifiers, and medical necessity before issuing payment or denial.

Step 3: Payment and Remittance Advice

- Once claims are processed, MACs issue Electronic Remittance Advice (ERA 835) detailing payment amounts, adjustments, and denial codes.

- Payments are typically made via Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) within 14–30 days of claim receipt.

- MACs also generate paper remittance summaries for smaller practices that do not use ERA files.

Step 4: Provider Education and Compliance Support

- MACs maintain ongoing relationships with providers through:

- Webinars and training sessions on billing updates and policy changes.

- Email listservs for regulatory announcements and fee schedule revisions.

- Help desk support for claim errors, NPI issues, or EDI rejections.

- They also publish LCDs (Local Coverage Determinations)—policy interpretations that clarify CMS rules for specific procedures or diagnoses within a jurisdiction.

Step 5: Appeals and Redetermination

- If a claim is denied, providers may file a first-level appeal (redetermination) with their MAC within 120 days of the denial notice.

- The MAC’s appeals unit reviews submitted documentation and either upholds or reverses the initial decision.

- Further appeals (Levels 2–5) move beyond the MAC to independent contractors, ALJs (Administrative Law Judges), and the Departmental Appeals Board.

Step 6: Program Integrity and Audit Coordination

- MACs coordinate with Recovery Audit Contractors (RACs), Comprehensive Error Rate Testing (CERT) contractors, and Zone Program Integrity Contractors (ZPICs) to detect improper payments and fraud.

- They perform data analytics and medical reviews to identify billing patterns that deviate from national norms.

- When issues arise, MACs issue demand letters or initiate overpayment recovery actions under CMS oversight.

Step 7: Digital Integration and Future Role

- MACs are increasingly central to CMS’s digital modernization strategy, including expanded use of:

- APIs and portal access for real-time claim status tracking.

- AI-assisted review tools to streamline audits and coverage determinations.

- Interoperability pilots to support data exchange across CMS systems and EHR platforms.

- Their evolution ensures Medicare payment operations remain efficient, secure, and scalable.

Summary Insight

MACs are not policymaking entities but executional agents—the link that turns federal reimbursement rules into consistent, timely provider payments. Their performance directly affects cash flow, compliance risk, and provider satisfaction across the healthcare ecosystem.

UPL in Medicaid Billing, Reimbursement, and Fiscal Limitations

The Upper Payment Limit (UPL) defines the maximum aggregate Medicaid reimbursement that states may pay to a class of providers. Within that ceiling, states distribute base and supplemental payments designed to stabilize hospitals and nursing facilities serving Medicaid populations.

While UPL programs create flexibility for states to support provider funding, they also introduce significant administrative and compliance complexities that affect billing accuracy, audit exposure, and long-term fiscal sustainability.

How UPL Affects Medicaid Reimbursement

- The UPL ceiling establishes the total amount of Medicaid reimbursement—both base and supplemental—that a state can pay to each provider class (e.g., inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, nursing facility).

- States often use UPL programs to make supplemental payments to public or governmental providers to compensate for Medicaid shortfalls.

- These payments help maintain access and provider solvency, but they must stay within the federal upper limit equivalent to Medicare payment benchmarks.

- CMS requires that all UPL payments be aggregate-based, not provider-specific, ensuring fairness and limiting the risk of overcompensation.

- Accurate UPL management supports budget neutrality, prevents federal disallowances, and preserves federal matching (FMAP) eligibility.

Funding and Payment Flow

- UPL payments are financed jointly through state and federal funds, with the state share often generated via Intergovernmental Transfers (IGTs) or Certified Public Expenditures (CPEs).

- Once CMS approves the state’s UPL demonstration, supplemental funds are distributed according to the approved schedule—commonly quarterly or annually.

- States must report total Medicaid payments for each provider class to confirm they do not exceed the UPL ceiling.

- Misreporting or excess payments can lead to recoupments or loss of federal matching funds, significantly impacting state Medicaid budgets.

Administrative and Technical Limitations

- UPL programs are data-intensive, requiring accurate cost report analysis, claims modeling, and Medicare payment simulations.

- Inconsistent or outdated cost data can distort UPL calculations, risking noncompliance with CMS thresholds.

- Because UPLs are aggregate-level limits, states must balance payments across multiple providers, making distribution complex and politically sensitive.

- Many states rely on external actuaries or consultants to manage data quality, increasing administrative costs and oversight complexity.

Compliance and Audit Exposure

- CMS and the Office of Inspector General (OIG) routinely audit UPL programs to ensure adherence to federal payment caps.

- Findings of excess payments or flawed methodologies can trigger federal disallowances, requiring states to repay millions in federal matching funds.

- States are expected to maintain transparent documentation, including the underlying data, cost models, and demonstration methodologies used in each UPL submission.

Common audit risks include:

- Outdated Medicare cost benchmarks

- Unclear differentiation between UPL and DSH (Disproportionate Share Hospital) funding

- Overreliance on estimates instead of auditable cost data

Fiscal Constraints and Reform Challenges

- UPL programs provide critical fiscal relief for Medicaid providers but remain structurally constrained by federal aggregate limits.

- As Medicaid increasingly shifts toward managed care, CMS continues to refine how UPL limits apply to non-risk and directed payment arrangements.

- Many states advocate for modernization to allow value-based or quality-linked UPL adjustments, aligning reimbursement with performance outcomes.

- However, proposed reforms must maintain budget neutrality and prevent the duplication of federal match funds across overlapping programs.

Policy and Systemic Limitations

- The complexity of UPL methodology can obscure payment transparency, making it difficult for stakeholders to trace funding from source to provider.

- CMS has emphasized greater public reporting and auditable traceability to ensure accountability.

- States face resource and timing challenges in updating UPL demonstrations, particularly under evolving Medicaid managed care and supplemental payment policies.

- Ongoing CMS guidance aims to reduce variation and strengthen national consistency across state UPL frameworks.

Key Takeaway

UPL programs are a fiscally vital but compliance-sensitive component of Medicaid reimbursement. They offer states a mechanism to reinforce provider networks and offset underpayment, yet demand rigorous documentation, audit readiness, and transparent calculation practices to avoid federal disallowances.

Effective UPL administration depends on accurate cost modeling, timely reporting, and coordinated oversight between states and CMS.

How the Upper Payment Limit (UPL) Shapes Quality, Access, and Equity in Medicaid Financing

Although the Upper Payment Limit (UPL) is a financial control mechanism, its impact extends beyond reimbursement ceilings. By influencing how states distribute supplemental Medicaid payments, UPL policy directly affects provider participation, hospital stability, and equitable access to care for low-income populations.

Effective administration of UPL programs ensures that fiscal safeguards do not undermine quality, access, or fairness across provider classes.

Balancing Fiscal Integrity with Provider Sustainability

- The UPL system promotes budget neutrality and accountability by capping Medicaid payments at Medicare-equivalent levels.

- When properly structured, it enables states to enhance provider reimbursement without breaching federal limits—helping sustain financially vulnerable hospitals and nursing facilities.

- However, misaligned or delayed UPL distributions can strain provider operations, particularly in safety-net and rural hospitals that rely on timely supplemental funding.

- CMS oversight seeks to maintain equilibrium between cost containment and provider viability, ensuring the UPL framework supports rather than destabilizes care delivery.

Impact on Provider Access and Participation

- Consistent and transparent UPL programs are essential for retaining provider participation in Medicaid, especially among public and teaching hospitals with high Medicaid volumes.

- States that manage UPL payments effectively can attract and retain providers, ensuring sufficient network capacity for beneficiaries.

- Conversely, inconsistent calculations or payment delays may deter participation and limit access to inpatient and long-term care services, particularly in underserved communities.

- UPL-driven supplemental funding helps prevent service closures and coverage gaps, maintaining equitable access at the state and regional levels.

Equity Across Provider Classes and Regions

- Federal UPL policy requires states to apply consistent methodology across provider classes—inpatient hospital, outpatient hospital, and nursing facility—to ensure fairness in supplemental distributions.

- Variability in state methodologies, however, can lead to regional disparities in funding levels, especially where data quality or cost-reporting standards differ.

- CMS encourages states to adopt standardized reporting templates and transparent demonstration methods to minimize inequities in provider treatment.

- Ongoing oversight aims to ensure that supplemental payments do not disproportionately benefit large systems at the expense of community-based or rural facilities.

Transparency, Accountability, and Public Oversight

- CMS’s emphasis on public reporting of UPL demonstrations reinforces transparency and stakeholder trust.

- States are encouraged to publish aggregate payment data, calculation methodologies, and audit findings to allow policy review and public accountability.

- Transparent UPL processes help mitigate perceptions of inequity and ensure that funding aligns with documented care costs and service needs.

- Regular federal and state audits strengthen program integrity, deterring misuse or politically influenced payment allocation.

Alignment with Quality and Value-Based Care Initiatives

- CMS has signaled growing interest in linking UPL mechanisms to quality and performance metrics within Medicaid reform initiatives.

- Some states are piloting models where a portion of UPL supplemental payments is tied to quality outcomes such as readmission rates or patient safety benchmarks.

- This evolution aligns UPL policy with CMS’s broader value-based purchasing strategy, supporting both financial integrity and measurable quality improvement.

- Future reforms may require states to demonstrate not only fiscal compliance but also improvement in care outcomes and equity indicators.

Equity and Access as Ongoing Policy Priorities

The UPL’s ultimate goal is to balance fiscal prudence with equitable access to Medicaid-funded care.

- Ensuring that supplemental payments reach high-need providers—without creating distortions or inequities—remains a key focus of CMS’s oversight.

- By reinforcing transparency, standardization, and quality linkage, UPL modernization contributes to a more equitable, efficient, and accountable Medicaid payment system.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Upper Payment Limit (UPL)

1. What is the Upper Payment Limit (UPL)?

The Upper Payment Limit (UPL) is the maximum aggregate payment that a state Medicaid program can reimburse certain provider classes—such as hospitals and nursing facilities—without exceeding what Medicare would have paid for the same services. It serves as a fiscal safeguard to ensure Medicaid spending remains within federal reimbursement boundaries.

2. How does the UPL work in Medicaid?

Under 42 CFR §447.272–§447.321, each state must calculate and demonstrate that total Medicaid payments for a class of providers stay below the UPL benchmark.

States compare Medicaid payments against Medicare-equivalent rates using cost reports and statistical models. CMS reviews these demonstrations annually to ensure aggregate compliance and fiscal integrity.

3. Which providers are affected by UPL limits?

UPL rules apply to three main provider classes:

- Inpatient hospitals

- Outpatient hospitals and clinics

- Nursing facilities

Each class has its own UPL calculation and compliance documentation. States may distribute supplemental payments within these classes, but total reimbursement cannot exceed the UPL threshold.

4. What are UPL supplemental payments?

UPL supplemental payments are additional Medicaid funds distributed to eligible providers—often public hospitals—to offset shortfalls between Medicaid base rates and estimated Medicare-equivalent costs.

These payments must remain within the UPL aggregate ceiling and receive CMS approval through a State Plan Amendment (SPA). They help sustain access and provider participation in Medicaid programs.

5. How are UPL demonstrations and approvals handled?

Each year, states submit UPL demonstrations to CMS Regional Offices, documenting calculation methodologies, cost sources, and aggregate payment levels.

CMS reviews and either approves, requests revision, or issues disallowances if payment caps are exceeded. Demonstrations ensure transparency, accountability, and compliance with federal matching requirements.

6. What happens if a state exceeds the UPL?

If CMS determines that a state’s Medicaid payments exceed the Upper Payment Limit, the federal share of excess payments must be recouped or offset through the disallowance process.

Repeated noncompliance can result in funding reductions, delayed approvals for State Plan Amendments, or increased audit scrutiny.

7. Why is the UPL important for Medicaid equity and fiscal management?

The UPL framework helps balance provider support and taxpayer protection.

By ensuring payments remain tied to Medicare-equivalent rates, UPLs prevent overcompensation while still allowing states to target supplemental funds toward safety-net and high-Medicaid-volume providers.

Properly managed UPL programs promote equitable reimbursement, budget stability, and continued access for vulnerable populations.