What is FFP (Federal Financial Participation) in Healthcare?

Federal Financial Participation (FFP) refers to the federal government’s share of funding for eligible Medicaid services and administrative activities. Under Medicaid, states pay for services upfront and then receive partial reimbursement from the federal government in the form of FFP, based on defined match rates and eligibility rules.

In practical terms, FFP is the financial backbone of Medicaid. It determines which services, programs, and administrative functions are financially sustainable for states, managed care organizations, and provider partners. For healthcare organizations, care management vendors, and public-sector stakeholders, understanding FFP is essential because it directly influences program design, documentation standards, and long-term funding decisions.

FFP does not apply uniformly across all Medicaid activities. Different services and functions qualify for different federal match rates, and only costs that meet federal requirements can be claimed. As a result, FFP shapes not just how Medicaid is paid for, but how care coordination, quality initiatives, and administrative workflows are structured across the healthcare system.

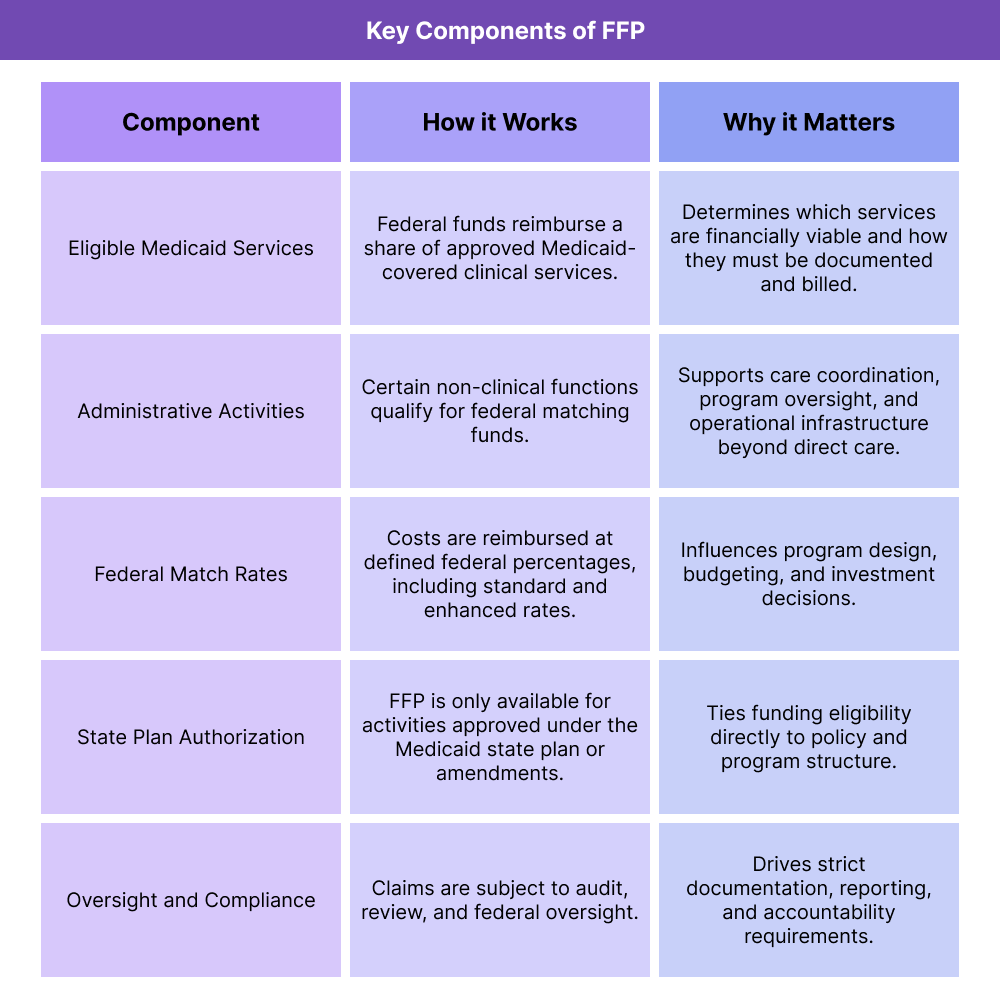

Key Components of Federal Financial Participation (FFP)

While FFP is often discussed as a single concept, it is best understood as a framework with several interconnected components. Each component affects how Medicaid programs are funded, how states design services, and how providers and vendors support compliance and reimbursement.

Eligible Medicaid Services

FFP applies to Medicaid-covered services that are included in a state’s approved Medicaid plan. These services may include primary care, behavioral health, hospital services, long-term services and supports, and certain care management activities. To qualify for FFP, services must meet federal requirements for medical necessity, provider qualifications, and documentation.

For providers and health systems, this means that delivering a service alone is not enough. The service must be structured, documented, and billed in a way that aligns with federal and state Medicaid rules in order for the state to receive its federal match.

Administrative Activities and Program Operations

In addition to direct clinical services, many administrative functions are also eligible for FFP. These can include activities such as care coordination, outreach, eligibility support, program oversight, quality improvement, and systems operations.

Administrative FFP is especially important for programs like Medicaid Administrative Claiming, care management initiatives, and technology investments that support Medicaid operations. However, administrative claiming comes with stricter cost allocation, documentation, and audit requirements, making accurate tracking and reporting essential.

Federal Match Rates

FFP is calculated using federal match rates that determine how much of a given cost the federal government will reimburse. The most common match rate is the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP), which varies by state and is adjusted annually based on economic factors.

Some activities qualify for enhanced match rates. For example, certain administrative functions, system development costs, or targeted program investments may receive a higher federal share. These enhanced rates can significantly influence how states prioritize programs and vendors.

State Plan and Approval Structure

FFP is only available for activities that are authorized under an approved Medicaid state plan or related federal approvals. States define how services are delivered and claimed through their Medicaid State Plan, State Plan Amendments, and other CMS-approved mechanisms.

From an operational standpoint, this means FFP eligibility is tied to policy design. If an activity is not clearly authorized, or if it drifts outside approved parameters, the associated federal funding can be delayed, reduced, or denied.

Oversight, Audits, and Compliance

Because FFP involves federal dollars, it is subject to oversight and audit at multiple levels. States must be able to demonstrate that claimed costs were allowable, properly allocated, and supported by adequate documentation.

For providers, care management organizations, and vendors, this translates into downstream requirements around time tracking, service documentation, reporting logic, and data retention. Weak controls or unclear workflows can expose states to disallowances, which may then cascade back to partner organizations.

How FFP (Federal Financial Participation) Works in Practice

Federal Financial Participation (FFP) is not a direct payment to providers. Instead, it is the mechanism through which the federal government reimburses states for a share of eligible Medicaid costs. In day-to-day operations, FFP works through a cycle of program design, service delivery, claiming, documentation, and oversight.

For healthcare organizations and vendors supporting Medicaid populations, the practical impact is simple: if the activity can’t be substantiated and claimed correctly, the federal match may be reduced, delayed, or denied.

Step 1: Program Design and Eligibility Alignment

FFP begins before any service is delivered. States structure Medicaid services, administrative programs, and care initiatives based on what is allowed under their Medicaid plan and applicable federal rules. To be eligible for FFP, a service or administrative activity must be clearly authorized and defined.

This step determines:

- What services qualify for federal match

- What administrative activities can be claimed

- How responsibilities are split across state agencies, managed care organizations, and provider partners

- What documentation standards will be required downstream

Step 2: Service Delivery and Administrative Work

Once programs are established, eligible services are delivered in clinics, health systems, community settings, and managed care networks. At the same time, eligible administrative work occurs behind the scenes—care coordination, outreach, program operations, eligibility support, quality activities, and system functions.

Operationally, this is where many organizations lose FFP eligibility: activities may be performed appropriately, but not tracked in a way that proves they were allowable, allocable, and properly tied to Medicaid.

Step 3: Cost Capture, Coding, and Cost Allocation

To claim FFP, states must capture costs and allocate them correctly. This includes separating:

- Medicaid-eligible costs vs. non-Medicaid costs

- Direct services vs. administrative activities

- Program-specific expenses vs. general overhead

Providers and vendors may not be filing federal claims directly, but their workflows often generate the underlying records that states rely on—timesheets, service logs, encounter records, task tracking, and reports.

When cost allocation is weak (or data is incomplete), organizations often face retroactive corrections, delayed claiming, or disallowances.

Step 4: Claiming, Reporting, and Federal Match

States submit Medicaid expenditure reports and supporting documentation to obtain their federal share. Depending on the activity, claiming may occur on a regular reporting cycle and may involve multiple systems, agencies, and contractor inputs.

In practice, FFP depends on:

- Clean, consistent documentation

- Strong data governance and retention practices

- Reporting that matches approved claiming methodologies

- Clear linkage between activities performed and costs claimed

Step 5: Review, Audit, and Ongoing Oversight

FFP is subject to ongoing review. Federal and state oversight entities can examine whether claimed activities were valid, whether costs were allocated appropriately, and whether the supporting records are sufficient.

From a business standpoint, this means FFP is a compliance-sensitive funding stream. It rewards strong operational discipline: documentation, role clarity, audit readiness, and consistent system configuration.

FFP in Billing, Reimbursement, and System Limitations

FFP shapes Medicaid financing, but it also influences the billing and reimbursement environment indirectly. Many organizations assume FFP is just “the match rate,” but operationally it drives what gets reimbursed, how programs are structured, and how aggressively documentation standards are enforced.

How FFP Influences Medicaid Reimbursement

FFP is the reason states can afford Medicaid at scale. States pay for services and then receive partial reimbursement from the federal government, based on applicable match rates.

The business implications show up downstream:

- States and plans are incentivized to design services that qualify for match

- Documentation and billing rules tend to be stricter where match eligibility is sensitive

- Program expansions often depend on whether a sustainable FFP pathway exists

- Funding decisions (including vendor investments) often follow enhanced match opportunities

Even when providers are paid through managed care arrangements, the underlying state financing still depends on FFP logic—meaning program rules, reporting requirements, and documentation expectations tend to reflect federal claiming realities.

Administrative Claiming and “Behind-the-Scenes” Funding

A major source of confusion is administrative FFP. Many care management, outreach, and operational functions can qualify for federal match—if they are tracked properly and tied to allowable categories.

This is where system design matters. Organizations often need:

- Consistent activity tracking and time capture

- Clear definitions of allowable tasks

- Structured reporting aligned to claiming methodologies

- Audit-ready records that show who did what, when, and why

Without these controls, even legitimate work may not be claimable—or may become risky in an audit.

System Limitations and Common Watch-Outs

Organizations often run into predictable pressure points that reduce or complicate FFP eligibility:

- Siloed systems: activity tracking lives outside the EHR, making it hard to verify work performed

- Inconsistent definitions: teams label the same activity differently, causing reporting errors

- Weak cost allocation discipline: costs can’t be reliably split between Medicaid and non-Medicaid work

- Limited audit readiness: records are incomplete, hard to retrieve, or not standardized

- Multi-agency complexity: state agencies, MCOs, and providers operate under different reporting practices

For vendors and partners, the key is building workflows that are both operationally realistic and financially defensible—so that the activities being performed can actually be supported in federal match claims.

How FFP Influences Quality, Access, and Equity in Healthcare

FFP is often framed as a financial mechanism, but it has real downstream impact on who gets care, what programs exist, and how quality initiatives are funded. The availability of federal match influences what states can scale and what providers can sustain—especially in Medicaid-heavy environments.

Access: What Services Can Be Sustained at Scale

Because Medicaid is jointly funded, FFP directly affects the scope of services states can offer and maintain. When match rates are favorable and claiming pathways are clear, states can more easily fund:

- Care coordination and case management initiatives

- Community-based supports that reduce avoidable utilization

- Workforce investments and operational infrastructure

- Program expansions targeted at high-need populations

When funding pathways are unclear or documentation requirements are burdensome, states may narrow services or create administrative barriers that indirectly reduce access.

Quality: How Improvement Programs Get Built and Measured

Quality programs require staffing, systems, reporting, and continuous improvement work—much of which depends on administrative infrastructure. FFP influences whether states and plans can:

- Invest in data systems and reporting capacity

- Support quality improvement operations

- Align incentives toward preventive care rather than reactive utilization

- Fund targeted initiatives tied to maternal health, behavioral health, chronic disease management, and more

In practice, strong FFP-aligned funding structures can make quality programs durable. Weak structures often result in short-lived pilots that disappear when funding gets complicated.

Equity: Resource Distribution and Administrative Burden

Equity impacts emerge when the administrative requirements tied to match eligibility create friction that not all organizations can absorb. Smaller clinics, rural providers, and under-resourced systems may struggle more with:

- Documentation burden

- Tracking requirements

- Staffing needed for reporting and audit readiness

- System integrations that larger organizations take for granted

That dynamic can widen gaps—where well-resourced systems can participate fully in Medicaid-funded initiatives while safety-net providers are left behind.

At the same time, when states intentionally use FFP to fund care coordination and infrastructure in underserved communities, it can be a powerful lever for equity—supporting access, continuity, and quality for populations that have historically been excluded from stable healthcare resources.

Frequently Asked Questions about FFP

1. What is FFP (Federal Financial Participation) in Medicaid?

Federal Financial Participation (FFP) is the federal government’s share of funding for eligible Medicaid services and administrative activities. States pay for Medicaid services upfront and then receive partial reimbursement from the federal government based on approved match rates and eligibility rules.

2. How does Federal Financial Participation work in Medicaid programs?

FFP works through a reimbursement model where states submit claims for eligible Medicaid expenditures and receive federal matching funds in return. The amount reimbursed depends on the type of service or activity and the applicable federal match rate, such as the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP).

3. What services and activities are eligible for FFP funding?

FFP can apply to both direct Medicaid services (such as medical and behavioral health care) and certain administrative activities, including care coordination, outreach, eligibility support, quality improvement, and program operations. Eligibility depends on federal rules and state Medicaid plan approval.

4. What is the FFP match rate and how is it determined?

The FFP match rate is the percentage of eligible Medicaid costs that the federal government reimburses. Most services are reimbursed at the state’s FMAP, which varies annually based on economic factors. Some activities qualify for enhanced match rates under specific federal programs or approvals.

5. How does FFP affect Medicaid administrative claiming and care coordination?

Many care coordination and administrative activities can qualify for FFP if they are tracked, allocated, and documented correctly. This is especially relevant for Medicaid Administrative Claiming programs, where states rely on detailed activity logs, time tracking, and reporting to support federal match claims.

6. Who is responsible for claiming and managing FFP?

States are responsible for claiming FFP from the federal government, but they rely on data, documentation, and reporting from managed care organizations, providers, and vendors. Errors or gaps at the provider or vendor level can affect a state’s ability to claim federal funds.

7. How does FFP influence Medicaid billing and reimbursement workflows?

FFP shapes how Medicaid programs are designed and reimbursed. Because federal match eligibility depends on compliance and documentation, states often impose stricter billing, reporting, and utilization controls to protect FFP. These requirements flow down to providers and health systems through contracts and program rules.

8. What are common compliance risks related to Federal Financial Participation?

Common risks include inadequate documentation, poor cost allocation, inconsistent activity definitions, and weak audit readiness. If costs cannot be clearly tied to allowable Medicaid activities, federal funds may be disallowed, creating financial risk for states and their partners.

9. How does FFP impact quality, access, and equity in Medicaid?

FFP determines which programs states can sustainably fund. Clear and flexible FFP pathways support access to care coordination, preventive services, and quality initiatives, while overly complex requirements can create barriers—especially for smaller or under-resourced providers serving high-need populations.