What is a Critical Access Hospital (CAH)?

A Critical Access Hospital (CAH) is a rural acute-care facility designated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to ensure essential hospital services remain available in underserved and geographically isolated communities.

CAH status is a specialized Medicare designation created to reduce rural hospital closures by offering enhanced Medicare reimbursement and flexible operating requirements.

To qualify as a CAH, a facility must meet strict federal criteria, including:

- Being located in a rural area or receiving a rural reclassification

- Maintaining no more than 25 inpatient beds

- Maintaining an annual average patient length of stay of 96 hours or less

- Providing 24/7 emergency services

- Meeting distance requirements—typically 35 miles from the nearest hospital, or 15 miles in mountainous or secondary-road regions

- Complying with the CAH Conditions of Participation (CoPs)

What distinguishes CAHs from standard acute-care hospitals is their cost-based Medicare reimbursement model, under which Medicare pays 101% of reasonable costs instead of the Prospective Payment System (PPS).

This payment structure stabilizes financial viability for rural hospitals that operate with low patient volumes and limited economies of scale.

Many CAHs also operate swing beds, allowing a single bed to serve both acute and post-acute (skilled nursing) needs under Medicare rules—improving care continuity while maximizing resource utilization in small facilities.

Critical Access Hospitals play a pivotal role in sustaining rural healthcare access, emergency readiness, and local health system resilience across the United States.

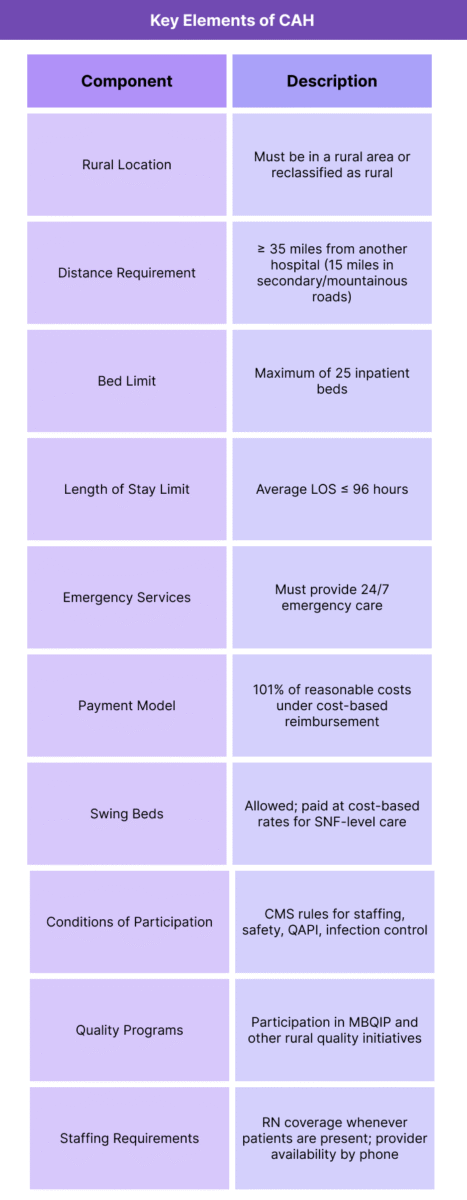

Key Components of Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs)

Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) operate under a specialized Medicare framework designed to preserve emergency and inpatient access in rural communities.

Their structure combines regulatory flexibility, stringent eligibility requirements, and a unique reimbursement model that protects low-volume hospitals from financial instability.

Below are the core elements defining CAH designation, operations, and Medicare payment policy.

1. CAH Eligibility and Designation Criteria

- To receive and maintain CAH status, a facility must meet federal statutory and regulatory requirements, including:

- Rural Location: Must be located in a rural area or qualify for rural reclassification through CMS.

- Distance Requirement: Typically 35 miles from another hospital; 15 miles in mountainous or secondary-road areas.

- Bed Limit: Maximum of 25 inpatient beds (excluding labor-and-delivery exceptions).

- Length of Stay: Average annual acute-care LOS ≤ 96 hours.

- Emergency Services: Must provide 24/7 emergency care.

- State Designation: Must be designated by the state as a CAH before CMS certification.

- These criteria aim to ensure CAHs are reserved for facilities serving communities with the greatest need.

2. Medicare Cost-Based Reimbursement Model

- The hallmark of CAH payment policy is cost-based reimbursement, under which Medicare pays:

- 101% of reasonable costs for inpatient, outpatient, and swing-bed services

- Enhanced payments for lab services furnished to outpatients

- Separate reimbursement for certain professional services in rural areas

- This model contrasts with the Prospective Payment System (PPS), where hospitals are paid predetermined rates regardless of actual cost.

- Cost-based reimbursement helps offset:

- Low patient volume

- High per-patient operating costs

- Limited service lines

- Challenges recruiting and retaining staff

3. CAH Conditions of Participation (CoPs)

- CAHs must comply with a distinct set of CMS Conditions of Participation, which outline expectations for:

- Clinical staffing (e.g., physician availability)

- Emergency services

- Patient rights and safety

- Quality assessment and performance improvement (QAPI)

- Medical record management

- Infection control

- Pharmacy and laboratory services

- Nursing services

- These requirements balance patient safety standards with rural operational realities.

4. Swing Bed Utilization

- Many CAHs operate swing beds, which allow hospitals to use the same bed for:

- Acute-care services, and

- Skilled nursing facility (SNF) care without requiring a separate unit

- Medicare pays CAHs cost-based rates for swing-bed services, making them a vital tool for:

- Post-acute recovery

- Rehabilitation

- Nursing care transitions

- Avoiding unnecessary transfers to distant facilities

- Swing beds are especially important in communities without local SNFs.

5. Staffing Structure and Emergency Readiness

- CAHs must:

- Maintain 24/7 emergency service capability

- Ensure a physician, NP, or PA is available by phone at all times

- Have a registered nurse on duty whenever a patient is in the facility

- Prepare for emergency transport and stabilization

- These staffing models reflect rural workforce constraints while preserving essential access.

6. Quality Reporting and Compliance Requirements

- CAHs are required to participate in quality improvement and reporting programs such as:

- MBQIP (Medicare Beneficiary Quality Improvement Project)

- Infection prevention initiatives

- Oversight through state survey agencies

- Annual recertification processes

- Although CAHs have fewer reporting obligations than PPS hospitals, quality monitoring remains a core compliance requirement.

7. Infrastructure and Operational Flexibilities

- To accommodate rural realities, CAHs benefit from certain flexibilities, including:

- Ability to maintain a limited number of beds

- Use of telehealth for specialty consultations

- Flexibility in diagnostic standards

- Alignment with community paramedicine initiatives

- These provisions help CAHs maintain viability with small patient volumes.

How Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) Work in Practice

Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) operate as the frontline healthcare hubs for rural communities, providing essential emergency, inpatient, diagnostic, and post-acute services in regions where no other hospital exists within safe travel distance.

Their day-to-day operations reflect the unique constraints of rural healthcare delivery: low patient volume, limited staffing, geographic isolation, and heavy reliance on Medicare reimbursement.

Below is the full operational workflow for how CAHs deliver care, sustain financial viability, and maintain compliance under the Medicare CAH designation.

Step 1: Rural Emergency and Stabilization Services

- CAHs serve as the first point of emergency care for rural residents.

- In practice, this includes:

- 24/7 emergency department coverage

- Rapid triage and stabilization

- Transfer protocols for trauma, stroke, cardiac, or specialty care

- Coordination with EMS, air transport, and regional hospitals

- Because CAHs often operate far from tertiary facilities, they play a crucial role in time-sensitive emergency response.

Step 2: Acute Inpatient and Observation Care

- CAHs maintain up to 25 inpatient beds, used for:

- Acute medical admissions

- Short-term recovery and monitoring

- Post-surgical follow-up (limited, based on capability)

- Observation stays

- Physician or NPP coverage must be available at all times, either onsite or by phone, with nursing staff in the building whenever patients are present.

- The 96-hour average LOS requirement shapes clinical workflows, encouraging efficient care and early transitions.

Step 3: Swing-Bed Utilization for Post-Acute Care

- One of the most distinctive CAH functions is the use of swing beds, which allow the hospital to convert an acute-care bed into a Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF)-level bed.

- In practice, swing-bed workflows include:

- Rehabilitation after surgery or hospitalization

- IV therapy

- Wound care

- Short-term skilled nursing support

- Local recovery to avoid long-distance SNF transfers

- For CAHs in areas with few or no SNFs, swing beds are pivotal to continuity of care.

Step 4: Outpatient, Diagnostic, and Ancillary Services

- To sustain operations, CAHs often offer:

- Laboratory and imaging services

- Outpatient clinics

- Rehab and therapy services

- Chronic care management programs

- Telehealth consultations with distant specialists

- Behavioral health services (increasingly common)

- Outpatient volumes help CAHs stabilize revenue given their limited inpatient census.

Step 5: Cost-Based Billing and Revenue Cycle Operations

- CAHs rely heavily on Medicare cost-based reimbursement, which shapes their billing operations:

- Claims are processed similarly to standard hospitals but reimbursed at 101% of reasonable costs

- CAHs receive cost-based reimbursement for outpatient, inpatient, and swing-bed care

- Lab services may receive separate enhanced payment

- CAHs must submit annual cost reports for reconciliation

- Strong financial stewardship is essential; documentation affects both payment and compliance.

Step 6: Staffing Models for Rural Sustainability

- Due to workforce shortages, CAHs leverage flexible staffing strategies:

- Cross-trained nurses for multiple departments

- On-call physician or NP/PA coverage

- Telehealth for specialty services

- Partnerships with larger health systems for clinical backup

- Rural staffing realities require efficiency while still meeting CAH Conditions of Participation.

Step 7: Quality, Safety, and Compliance Operations

- CAHs must maintain compliance with Medicare CoPs and state survey requirements, including:

- Quality Assessment and Performance Improvement (QAPI)

- Infection control policies

- Patient safety protocols

- Annual surveys by state agencies

- Ongoing CAH recertification

- Participation in MBQIP helps CAHs benchmark quality metrics while maintaining rural-appropriate reporting thresholds.

Step 8: Coordination With Rural Health Networks

- CAHs frequently participate in:

- Regional referral networks

- Telehealth partnerships

- EMS collaborations

- Community health programs

- Rural health clinic (RHC) integration

- Public health preparedness initiatives

- These partnerships help CAHs extend reach and maintain service continuity in low-resource environments.

Step 9: Operational Constraints and Risk Points

- CAHs must continuously manage constraints such as:

- Small margins despite cost-based reimbursement

- Workforce shortages

- Limited specialty coverage

- Aging infrastructure

- High fixed operating costs distributed across low patient volumes

- These vulnerabilities make CAHs sensitive to policy changes, staffing disruptions, and emergency surges.

CAHs in Medicaid Billing, Reimbursement, and System Limitations

Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) rely heavily on their specialized Medicare reimbursement structure to remain financially viable in rural settings.

While the cost-based payment model provides stability, CAHs still face significant reimbursement limitations, administrative burdens, and systemic vulnerabilities that shape their fiscal health.

Because CAHs often operate with low patient volumes, limited staffing, and high fixed costs, even small changes in documentation, cost reporting, or regulatory requirements can meaningfully impact their financial performance.

How Medicare Pays CAHs

- Unlike PPS hospitals that receive fixed DRG/APC rates, CAHs are reimbursed at:

- 101% of allowable reasonable costs for inpatient and outpatient services

- Cost-based reimbursement for swing-bed SNF-level care

- Separate cost-based payment for outpatient lab services

- Professional services billing that may follow different rules depending on physician arrangements

- This payment model helps offset:

- Low census

- High per-patient operating cost

- Staffing inefficiencies

- Lack of specialty services

- Geographic barriers

- However, cost-based reimbursement requires strict adherence to documentation and annual cost-report accuracy.

Cost Reporting and Reconciliation Challenges

- All CAHs must submit an annual Medicare Cost Report, which determines:

- Final reimbursements

- Cost-to-charge ratios

- Settlements and recoupments

- Reasonable cost adjustments

- Allowable vs. non-allowable expenses

- Common challenges include:

- Complex allocation of overhead costs

- Shifts in service line utilization

- Maintaining supporting documentation

- Managing interim payments vs. final settlement

- Avoiding misclassification of non-reimbursable costs

- Errors can lead to large retroactive recoupments, affecting financial stability.

Swing-Bed Reimbursement Considerations

- Medicare pays CAHs cost-based rates for swing-bed services, unlike SNFs that receive per-diem PPS payments.

This creates advantages but also operational nuances:- High reimbursement can stabilize CAH finances

- Overreliance on swing beds may attract audit support scrutiny

- Documentation must support SNF-level medical necessity

- Low occupancy can reduce efficiency despite favorable payment rules

- Swing beds are strategic but require strong compliance oversight.

Outpatient Billing Complexities

- Even though CAHs receive cost-based reimbursement, outpatient billing still requires:

- Accurate HCPCS coding

- Compliance with OPPS guidance where applicable

- Charge capture integrity

- Detailed documentation to justify costs

- Adherence to supervision and incident-to rules

- Revenue cycle complexity increases when CAHs run multiple on-campus and off-campus clinics.

Limitations and Vulnerabilities in CAH Reimbursement

- Key financial vulnerabilities include:

- Small service volumes magnify the impact of billing errors

- Limited specialty services restrict diversification of revenue streams

- Dependency on Medicare and Medicaid increases sensitivity to policy changes

- Rural staffing shortages drive up labor costs

- High fixed expenses spread across few patients inflate the cost base

- Aging infrastructure requires capital investments CAHs often cannot afford

- Telehealth billing variability depending on rural/originating site rules

- These factors make CAHs more financially fragile than PPS hospitals.

Impact of Operational Constraints

- Many CAHs struggle with:

- Limited coding and billing staff

- Difficulty maintaining compliance documentation

- Frequent turnover affecting cost-report continuity

- Inadequate technology for analytics and revenue cycle optimization

- Challenges meeting quality reporting expectations (MBQIP)

- Because Medicare cost-based payments are retrospective, cash flow becomes sensitive to:

- Interim payment rate changes

- Timing of settlements

- Audit findings

- Service fluctuations due to seasonal or demographic factors

Audit Exposure and Compliance Risks

- CAHs face audits from:

- MAC medical review units

- UPICs

- TPE contractors

- RACs

- State survey agencies

- Cost report auditors

- Common risk areas include:

- Failure to meet CAH designation criteria

- Non-compliance with 96-hour LOS requirement

- Improper allocation of overhead costs

- Questionable swing-bed utilization

- Inconsistent documentation for emergency or outpatient services

- Provider-based clinic billing issues

- Audit findings can jeopardize both financial stability and CAH certification.

Key Takeaway

While cost-based reimbursement is the backbone of CAH sustainability, it comes with significant administrative and compliance obligations.

The CAH model protects rural access but is financially vulnerable to documentation gaps, audit findings, cost-report inaccuracies, and operational constraints tied to workforce shortages and low patient volumes.

Maintaining CAH status—and the enhanced reimbursement it provides—requires meticulous cost reporting, strong compliance processes, and continuous monitoring of rural health policy changes.

How CAHs Influences Quality, Access, and Equity in Medicaid Financing

Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) are central to sustaining healthcare access and emergency readiness in America’s rural communities.

Because CAHs operate in regions with limited healthcare infrastructure, provider shortages, and long travel distances, their performance directly affects quality of care, health equity, and community health outcomes.

The CAH program was created not only to stabilize rural hospital finances, but to preserve equitable access to essential medical services for populations that historically experience worse health outcomes and greater structural barriers.

Preserving Access in Underserved Rural Communities

- CAHs serve as the sole local hospital for many communities.

- Their presence ensures:

- Immediate access to emergency and urgent care

- Stabilization before transfer to distant tertiary centers

- Local inpatient beds for acute conditions

- Available swing-bed services for post-acute recovery

- Access to diagnostic imaging, labs, and basic outpatient care

- Without CAHs, many rural residents—particularly older adults and those with chronic conditions—would face dangerous delays in receiving care.

Reducing Health Disparities Linked to Geography

- Rural populations experience:

- Higher mortality rates

- Increased prevalence of chronic disease

- Greater socioeconomic challenges

- Longer distances to specialty care

- Increased rates of uninsurance or underinsurance

- CAHs help mitigate these disparities by providing:

- Essential emergency services within reachable distance

- Telehealth connections to specialists

- Local chronic-care management programs

- Swing-bed rehabilitation that avoids long-distance transfers

- In this way, CAHs serve as a structural intervention in rural health equity.

Emergency Preparedness and Community Resilience

- CAHs function as rural emergency anchors, offering:

- Trauma stabilization

- Emergency care 24/7

- Coordination with EMS, air transport, and regional trauma networks

- Disaster readiness for natural disasters, weather emergencies, and community crises

- Many CAHs are the only medical facility positioned to respond during community-wide emergencies—a critical component of equitable, geographically distributed emergency response.

Impact of Workforce Shortages on Quality and Equity

- Rural areas face severe shortages in:

- Primary care physicians

- Non-physician clinicians

- Nurses

- Behavioral health providers

- Specialty medical staff

- These shortages affect:

- Wait times

- Access to specialty care

- Preventive care utilization

- Care continuity and follow-up

- Quality reporting capacity

- CAHs often rely on telehealth, traveling clinicians, and cross-trained staff to fill gaps—innovations that help maintain quality despite limited resources.

Financial Fragility and Risk of Hospital Closures

- Rural hospital closures disproportionately affect:

- Low-income communities

- Agricultural regions

- Tribal communities

- Aging populations

- Areas with high chronic disease burden

- Regions dependent on Medicare and Medicaid

- CAH designation serves as a policy tool to prevent closures by offering 101% cost-based reimbursement.

However, closures continue to occur—often in communities that either cannot obtain or do not meet CAH criteria—worsening geographic inequities.

Equity Concerns Related to Distance Requirements

- The CAH program’s distance rule (35 miles / 15 miles secondary roads) creates equity trade-offs:

- Communities slightly too close to another hospital may still lack realistic access due to transportation barriers.

- Geographic rules do not account for weather, income, terrain, or infrastructure challenges.

- Some rural minority populations remain underserved despite being “ineligible” for CAH coverage.

- CMS and rural health advocates continue to debate reforms to balance geographic fairness with program integrity.

Quality Reporting and Rural Performance Improvement

- CAHs participate in rural-focused quality programs such as MBQIP, which helps:

- Benchmark CAH performance

- Identify gaps in ED care, infection control, and patient safety

- Evaluate rural-specific quality metrics

- Encourage participation in improvement collaboratives

- Although CAHs have fewer reporting requirements compared to PPS hospitals, quality oversight ensures rural patients receive safe, high-quality care.

Key Insight

CAHs are more than small hospitals—they are lifelines for rural communities.

Their ability to maintain essential services directly shapes rural health equity, emergency preparedness, and long-term patient outcomes.

Yet persistent challenges—workforce shortages, financial fragility, geographic isolation, and limited resources—continue to threaten equitable care delivery in rural America.

Strengthening CAHs is essential to ensuring rural residents receive timely, safe, and accessible healthcare regardless of geography.

Frequently Asked Questions about CAHs

1. What is a Critical Access Hospital (CAH)?

A Critical Access Hospital (CAH) is a small, rural acute-care hospital designated by CMS to ensure essential healthcare services remain available in geographically isolated communities.

CAHs receive cost-based Medicare reimbursement and must meet federal criteria for location, bed limits, staffing, and emergency services.

2. How does a hospital qualify for CAH status?

To be certified as a CAH, a facility must:

- Be located in a rural area or receive rural reclassification

- Be at least 35 miles from the nearest hospital (15 miles in mountainous or secondary-road areas)

- Maintain no more than 25 inpatient beds

- Provide 24/7 emergency services

- Maintain an annual average length of stay of 96 hours or less

- Meet all CAH Conditions of Participation

Both state and CMS approval are required.

3. How are CAHs reimbursed by Medicare?

CAHs are reimbursed at 101% of reasonable costs for:

- Inpatient services

- Outpatient services

- Swing-bed SNF-level services

- Most lab services

- Some professional services depending on billing arrangements

This model helps stabilize finances in low-volume rural facilities.

4. What is the purpose of the 96-hour rule for CAHs?

The 96-hour annual average length-of-stay rule ensures CAHs focus on short-term acute care and transfer patients requiring prolonged or complex hospitalization to larger facilities.

Failure to meet this requirement may jeopardize CAH certification.

5. What are swing beds in a CAH?

Swing beds allow CAHs to use the same inpatient bed for:

- Acute-care services, and

- Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF)-level post-acute services

This flexibility enables local rehabilitation and recovery for rural patients and is reimbursed at cost-based rates.

6. What services do CAHs typically provide?

Common CAH services include:

- Emergency stabilization

- Acute inpatient care

- Observation services

- Swing-bed care

- Outpatient clinics and imaging

- Rehabilitation therapies

- Telehealth consultations with specialists

CAHs adjust their services to match community needs and workforce availability.

7. Why do CAHs receive cost-based reimbursement instead of PPS rates?

Because rural hospitals operate with low patient volumes, high fixed costs, and limited specialty services, PPS rates are often insufficient to cover operational expenses.

Cost-based reimbursement helps ensure rural residents have access to hospital-level care.

8. What are the common compliance risks for CAHs?

CAHs frequently face compliance challenges related to:

- Failing to meet the 96-hour LOS limit

- Distance requirement misinterpretation

- Inaccurate or incomplete cost reports

- Swing-bed documentation gaps

- Staffing and supervision issues

- Emergency services deficiencies

- Survey findings from state agencies

These risks may trigger audits, recertification actions, or corrective plans.

9. Does a CAH have to participate in quality reporting?

Yes. CAHs must engage in quality improvement and typically participate in:

- MBQIP (Medicare Beneficiary Quality Improvement Project)

- Infection control reporting

- State survey and certification programs

While reporting burden is lighter for CAHs than PPS hospitals, quality oversight is required.

10. Can a CAH lose its designation?

Yes. CAHs can lose certification if they fail to meet:

- Location or distance criteria

- Bed limits

- LOS requirements

- Emergency service standards

- Conditions of Participation

- Cost-reporting accuracy standards

Losing CAH status significantly impacts reimbursement and financial viability.

11. How does CAH status affect community health?

CAHs sustain local access to emergency and inpatient care, reduce travel burdens on rural residents, support chronic disease management, and provide vital diagnostic and outpatient services—making them central to rural health equity.